History of Lowell’s Libraries

General Library History

Even before the United States existed, books were an expense that most did not have access to. Those who were wealthy or were members of the clergy were the most likely owners of books.

In 1731, Benjamin Franklin helped to bring the concept of a membership library to the colonies. These were associations of dues paying members who pooled their resources to buy books, rent space, and pay librarians to manage the collection. He and his cohorts established the Library Company of Philadelphia that year, which was the first American subscription library.

He was an advocate for libraries and helped to create the first lending library of a sort. In 1790, he donated a collection of books to what is now known as Franklin, Massachusetts for their library. The town originally asked him for a bell for the town steeple, but Franklin felt that “sense” was better than “sound.” On November 20th 1790 those attending Franklin’s town meeting voted to lend the books to all Franklin inhabitants free of charge. This vote established the Franklin collection as the first public lending library in the United States.

Other firsts:

- Sturgis Library in Cape Cod is the oldest building housing a public library in the United States with the original house being built in 1644

- The Library Company of Burlington, New Jersey has a charter that was received in 1758 and they built the first library building in New Jersey in 1789

- The oldest library in American began with a 400-book donation by John Harvard, a clergyman, who later had this collection be the foundation of a university named after him.

- In 1800, the Library of Congress was established as part of an act of Congress to move the capital from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C. President John Adams approved the use of $5,000 for books for the use of Congress. While the books were lost in the War of 1812 when the capitol was burned in 1814, former President Thomas Jefferson offered to sell his personal collection of nearly 6,500 books to restock it.

- The Darby Free Library in Darby, Pennsylvania, claims to be “America’s oldest public library, in continuous service since 1743.”

- Peterborough, New Hampshire’s library was established in 1833 by a vote of the town as the first tax-supported free public library.

- The Scoville Memorial Library in Salisbury, Connecticut, also claims to be the first publicly funded library in the United States and was established in 1803.

- The Boston Public Library claims a number of firsts

- The first publicly supported free municipal library in the world – 1848

- first library to establish space specifically for children

And there are so many more.

What existed before the Public Library?

The original libraries of Lowell were one of multiple formats:

- Subscription services

- Private libraries – like those in private clubs, benevolent societies and churches. The ones in churches were both pastor and parish libraries.

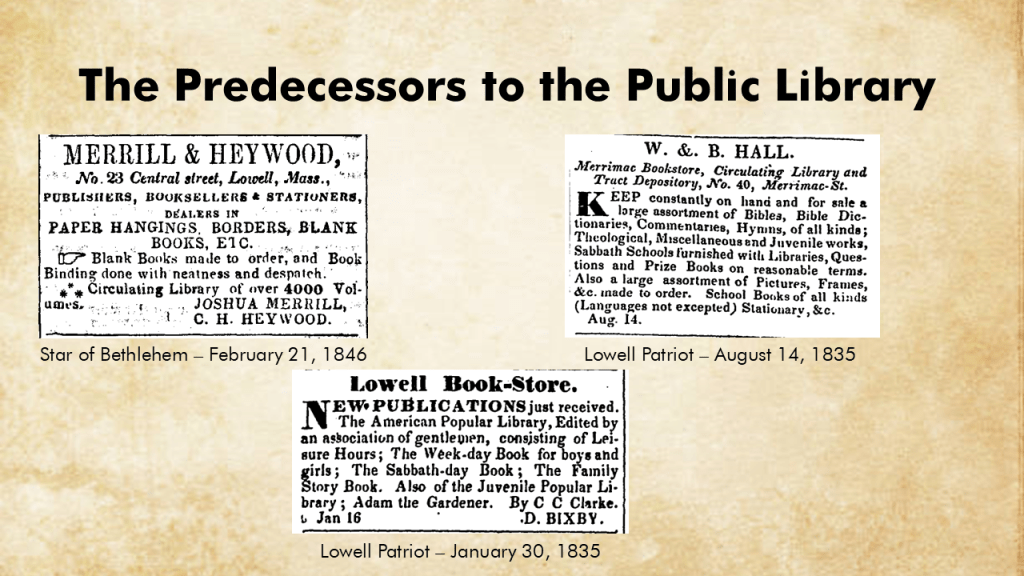

- Circulating libraries were run through various stores, including Bixby and Whiting. The Lowell Circulating Library at Stevens & Co. was established in 1834 with 2,000 volumes tied to the periodical bookstore.

- The Merrimack Corporation Reading Room for Females opened in 1844.

In 1829, Thomas Billings published his own Catalogue of Books, Belonging to Thomas Billings’ Circulating Library, which had approximately 700 volumes. This bookseller was located at 11 Merrimac Street.

Additional catalogues were created by

- Lowell Circulating Library at Lowell Bookstore – Tyler’s Building – 1834

- Upton Circulating Library at the Union Bookstore – 18 Central – 1841

- Anne’s Church – 1845 – Rector’s Library & Sunday School Library

- Worthen Street Methodist Episcopal Church – Sunday School Library – 1847

- Lowell Circulating Library connected with the Central Bookstore – Powers, Bagley & Co. – 1848

- Middlesex Mechanics Association – 1840, supplement 1846, 1851, 1853, 1856, 1860

- the First Unitarian Society – 1854, 1860

- Appleton Street Parish Library – 1863

- Lowell City School Library – 1845, supplement in 1855, 1858, and a supplement in 1860, 1865, 1869, and 1870, 1873 with supplements in 1875, (probably) 1878, and 1879.

Bookstores within the first 20 years of the city included

- Stevens & Co – Central (1834)

- Billings’ Lowell Bookstore – 11 Merrimac Street (1830) – later Bixby’s Lowell Book-store (1835) – 11 Merrimac

- Randall Meacham & Bernard (1832) Meacham & Mathewson Bookstore & Bindery – No. 5 Union Building on Central Street (1846)

- Olive Sheple Bookstore – Central Street

- Thomas Sweetser Variety & Bookstore – Merrimack St. at Wyman’s Exchange

- Merrill & Heywood – 23 Central Street (1846)

- W & B Hall Bookstore & Circulating Library – No. 40 Merrimac (1835)

- Other bookstores/sellers include John Botfur on Merrimack, Rand & Southmayd at 40 Merrimack (1834) , the Franklin Bookstore in the Union Building on Central St., Stevens & Co, bookseller and circulating library at 18 Central Street, the Theological Bookstore (D.G. Holmes & Co.), and Abijah Watson at the Corner of Central & Middle.

The First Library at Old City Hall

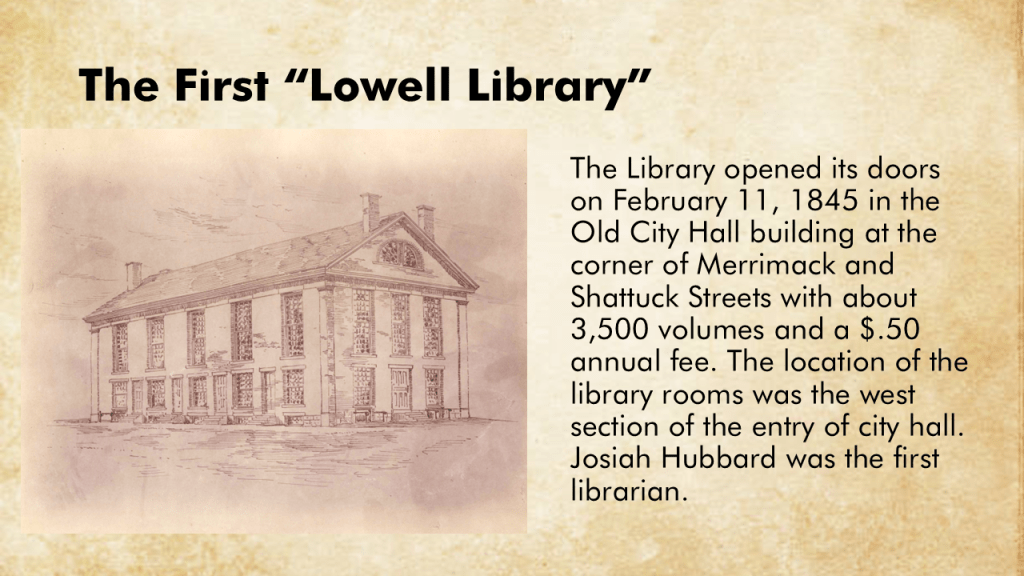

The Lowell City School Library was established as one of the few libraries in the country that “owes its existence to municipal action” per Hurd. It was not created due to an endowment, donation of a collection, or other means, that through the established passage of a City ordinance on May 20, 1844 under Mayor Elisha Huntington. This followed the resolves of 1842, 1843, and 1844 of the Legislature specifically related to school libraries. The Board of Directors were organized on the 7th of June 1844. The resolutions allowed for the library to be established with $1215 from the State of Massachusetts and another $2000 from the city as reported in the Lowell Operative on January 25, 1845.

The ordinance provided for a board of 7 directors with the official name as the Lowell City School Library due to the legislation. The original board minutes included Homer Bartlett and Josiah G. Abbott, who are replaced in the public notice by Nathan Crosby and John Graves before the library opened. The public notice included Huntington as mayor, John Clark the president of the Common Council, Julian Abbot, Thomas Thayer, and Abner Brown.

The Library opened its doors on February 11, 1845 with 3,500 volumes and a $.50 annual fee. The location of the library rooms was the west section of the entry of City Hall. Josiah Hubbard was the first librarian. The original schedule was Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday (unless a public festival or customary holiday interferes) from 2 till 5 and 7 to 9 in the afternoon.

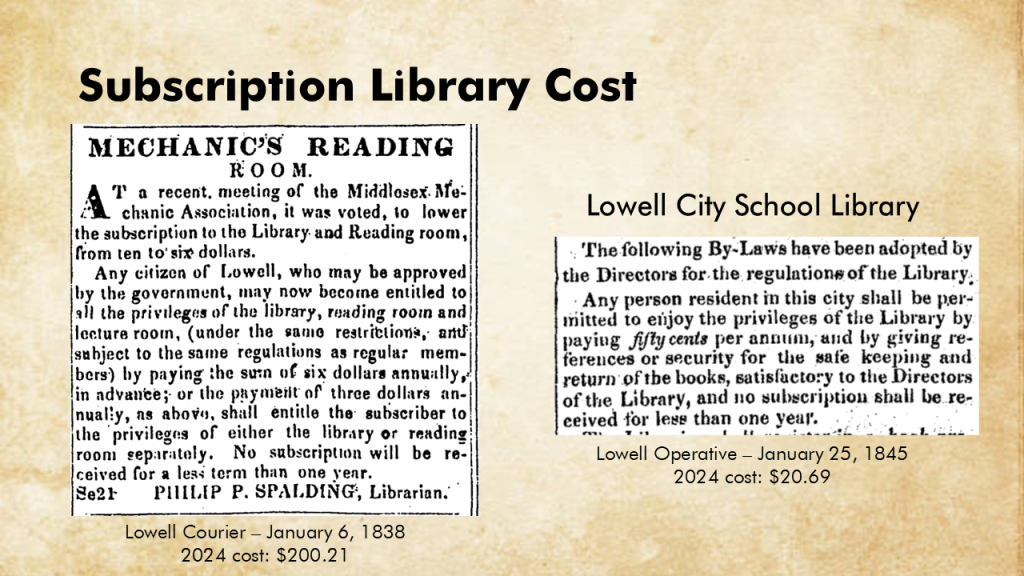

The concept of a “free” library was limited at the beginning of public libraries, but to give you an example of costs the subscription for the Merrimack Mechanics’ Reading Room was $6/yr (about $200 in today’s dollars) and the library was $.50 or about $20 in 2024 funds. Henry Miles’ Lowell as it was and as it is referenced it as a bargain in 1845.

The initial collection of the Library was purchased through one of the city’s circulating libraries. For the first 15 years of the budget, though, many of the purchases were made by the board (who were then reimbursed) for any volumes added to the collection. Julian Abbott, Esquire, made the most purchases, followed closely by the Librarian, Josiah Hubbard. A smaller number of purchases were fulfilled by the local booksellers in the city.

Challenges at the beginning – regardless of the library or the booksellers getting people to return items was a challenge – multiple advertisements in early papers called for the return of items. There was often black lists published in local papers. Once such example was the Lowell Circulating Library put out an advertisement in the Lowell Journal on January 14, 1834.

Source: History of Lowell and Its People – by Colburn

Another challenge was lack of adequate space. As early as 1853, the library had to be moved from its original location to a larger space on the third floor of City Hall.

Throughout the library’s history, the name has changed slightly. The original name of Lowell City School Library held for about 15 years, when it was changed to the City Library of Lowell, which was in place for over 120 years before it was renamed the Pollard Memorial Library in remembrance of long-time city councilor and former mayor Samuel S. Pollard.

In 1862 there were issues with insufficient light in the library room and the directors were addressing it. Two skylights were added over the summer. At the same time, they were interested in creating a library seal. Led by a committee, William Paul, a designer at Hamilton Print Works, created 12 designs. The official seal bears the name of the library, the date of establishment (1844), an ancient lamp in the style of the one that was found in the ruins of Pompeii, the flame of which heads towards the motto “Fiat Lux” (Let there be light). It was formally engraved by Messers. Mitchell of Boston.

During the Civil War and shortly thereafter, the Library hosted various artifacts related to the “war of rebellion” include pamphlets, trophies, confederate bank notes, rebel swords, and more.

In 1864, it was voted to make the library free to the City Councilors because “every possible aid should be given to cultivate the intelligence and morality of the people… it is not less necessary to make liberal provision to encourage the virtues requisite for national power, to counteract and reform the vices which are fostered by the condition of our country, and to prepare the people to act upon the great questions… these objects must be promoted by the education of adult life, in which free public libraries are, or should be, the most efficient agencies.”

In 1866, suggestions were being made to offer a public library reading room for the men of the city.

The Library at the Hosford Building

In 1872, the library relocated to the Masonic Temple in the Hosford Building (72-74 Merrimack St.). The initial contract was for 10 years at a rate of $1200/yr. (about $40,000/today). The library was here for nearly 20 years. There were issues within the building including a fire (1891) with $13,500 worth of lost materials and water damage (1886) – a burst steam pipe in the Directors’ office badly damaged books, pictures, and furniture.

Even though the City Councilors had free access to the library since 1864, it took time for that free service to be offered to the residents of Lowell, even though the Directors were advocating for it. There was discussion about this for a number of years including introducing a question in 1878 and the annual subscription fee ended in 1883. Due to a lack of space in the Hosford building, a reading room was established at Palmer & Middle, later another one was offered on John Street. If you look at early editions of the library’s catalog, you’ll see that the items were organized by number only. In 1883, the catalog was reformatted using the “new” Dewey Decimal classification system, which is still used in part today. Card catalogs were put into place versus publishing a catalog with a series of supplements. Books were added both under an author card and a subject card. The initial batch were all handwritten and completed in 1882 – nearly 70,000 cards. Additionally, the library began to offer book lists (light and heavy reading alternatives) and reading lists by subjects. New typewritten cards were started in 1887.

According to the Statistics of Public, School and Society Libraries, published in 1886, Lowell had eleven libraries for residents.

- the City Library (1844) with 30,000 volumes

- Coggeshall’s Circulating Library (1870), which was a subscription library, with 1,000 volumes

- Middlesex County Law Library (1850) with 900 volumes

- Middlesex Mechanics Association Library (1825/1827) with 20,000 volumes

- the Old Ladies Home (1878) with 300 volumes

- Rector’s Library at St. Anne’s Church (1860) with 2,000 volumes

- Reform School Library (1870) with 750 volumes

- St. Patrick Female Academy (1852) with 600 volumes

- Wentworth Library (Lowell Bar Association) (1875) with 400 volumes

- Young Man’s Catholic Library Association (1855) with 1,000 volumes

- Young Men’s Christian Association (1868) with 1,200 volumes

By 1883 a reading room for men was opened on October 17th on Middle and Palmer Streets. It took until 1888, for a reading room for women to be established.

Another ordnance was introduced in 1886, with the choice of the Librarians was removed from the City Council and placed in the hands of the directors. On April 17, 1888, the Trustees were incorporated by the legislature. At the suggestion of Mayor Charles D. Palmer, an act was passed entitled “An Act to Incorporate the Trustees of the City Library of Lowell,” which was approved.

The Trustees have had various expectations of authority over the years and have adapted their bylaws with changes in Lowell government. In 1898, the City solicitor was arguing that the library was an independent organization as a result of the establishment of the trustees the year before and its debts were their own and not the city’s. Also, the purchasing agent for the city refused certain library purchases that year, but the solicitor did support the trustees to be able to expend their money appropriately. I haven’t yet found any documentation that these arguments continued into the 20th century.

Middlesex Mechanics Association

The Middlesex Mechanics Association was incorporated in 1825 on petition of 80 mechanics initially focused on the county of Middlesex, but ended up being confined to Lowell. It was initially confined to mechanics only, with even overseers being ineligible for membership. Women were also excluded from membership until 1884 – they were allowed subscriptions to the library, but not the reading room. There were changes in those first years as to who could be included in membership. By 1834, men of influence became interested in the association and 220 new members were added. The Proprietors of Locks and Canals gave it land on Dutton Street, and by 1835, the building was erected. Donations from various manufacturing companies were made and Kirk Boott of the Merrimack Company was a prominent benefactor.

The first story and basement of this building were rented as stores, while the second story and attic were used by the association. By 1870 that changed and the association used the first story for a banquet room and anterooms. The hall on the second story of the building was very popular and was known for the amazing portraits of George Washington, Nathan Appleton, John A. Lowell, Patrick T. Jackson, James B. Francis, and Kirk Boott.

The library was established first in 1827 and Thomas Billings was elected as the librarian (at a salary of $6/year). At the start, the library had no building so were kept in rooms that also served other purposes like in 1833 they were in the counting-room of Warren Colburn, agent of the Merrimack Company. When the library moved into the Association building in 1835, about 725 books were made available in a low room on the third floor, where they stayed until a renovation in 1870. The library was mainly supported by donations in its earliest day, including donations from Abbott Lawrence, Kirk Boott, Charles L. Tilden, Charles Brown, and more. The library began to support its purchases with lecture courses that became very popular. Additional support for the library came from assessments, rentals, new memberships and subscriptions. The card catalogue and charging system started in 1880, which was a few years before the public library. Activities like a Japanese Tea Party in 1878 and Hungarian Band Concert in 1883 supported the purchases of materials for the library. In the late 1880s, an attempt was made to attract children to “wholesome reading” and an alcove of 1,000 volumes was set aside for their use. In 1890, the library had over 20,000 volumes.

When the City Library was made free in 1883, in put the Association library at a disadvantage and by 1896 they dissolved. It is important to point out that even though women were prohibited from membership for such a long time period, they were able to use the library, though not the reading rooms. The librarians of the Association can be found in Hurd’s History of Middlesex County, but of special note to this director was that they had female directors in 1871 to 1872 (Miss. Merriam) and 1872 until the 1890s, Miss M. E. Sargeant, which beats the female head of the library at the public library by almost 90 years. The first female acting director at the Lowell City Library was Catharine Conway who from documentation served for 2 years. A circulation clerk, Harriet F. Hill was selected at the City Library in 1882, though it was seen as a “new departure” for the board. By 1886, she was given the title Assistant Librarian.

The reading room was established in 1837. In the beginning the reading room was in the front portion of the second story, where the library was circa 1890, previous to which it was located above it. After a renovation in 1870, the reading room was moved to the backside of the second story. After the Civil War, it had more periodicals and magazine literature instead of the newspapers of the early years.

The Association often held lectures and also hosted 4 exhibitions of mechanic arts and inventions. Prizes were distributed and 8 gold medals were conferred, 65 silver medals and 210 diplomas. The first of the lectures were presented by Warren Colburn, author of school-books and agent of the Merrimack Mills.

When the Merrimack Manufacturing Association dissolved in 1896, parts of its collection including the portraits were donated to the City of Lowell and still appear in the Library and City Hall today.

Other Libraries in the City before the turn of the 20th century

There was a Young Men’s Catholic Library Association in the city started in 1854 and running through the latter part of the 19th century. It had about 1,000 volumes and was focused on the “literary wants of the young Irishmen of Lowell.”

The Old Residents’ Historical Association of Lowell had about 500 volumes in 1890 and its library was held in the office of Alfred Gilman, Esquire. It had a very limited number of patrons. It eventually evolved into the Lowell Historical Society and what remains of that early collection is housed at the Center for Lowell History in the Mogan Center.

The Library of the Middlesex North Agricultural Society was a small library that lasted about 2 years with 350 volumes. Due to its distance from the farms, it was not heavily used and the collection was eventually absorbed the Middlesex Mechanics’ Library.

The Library of the Young Men’s Christian Association of Lowell had about 600 volumes in 1890 after 400 items were discarded as being “worthless.”

The physicians of the city attempted to create a medical library of 250 volumes and a large number of pamphlets, but due to lack of support, those items were absorbed by the City Library.

The People’s Club of Lowell had 2 branches – the men’s branch was on John Street with 1100 volumes, and the women’s branch on Merrimack Street in the Wyman Exchange had 322. These libraries contained historical, biographical and story books, as well as magazines. From what I can find of these reading rooms in the City Directories, they started around 1872 with the ladies’ reading room closing around 1918 after moving to various locations downtown including the Runels building and another Merrimack Street location.

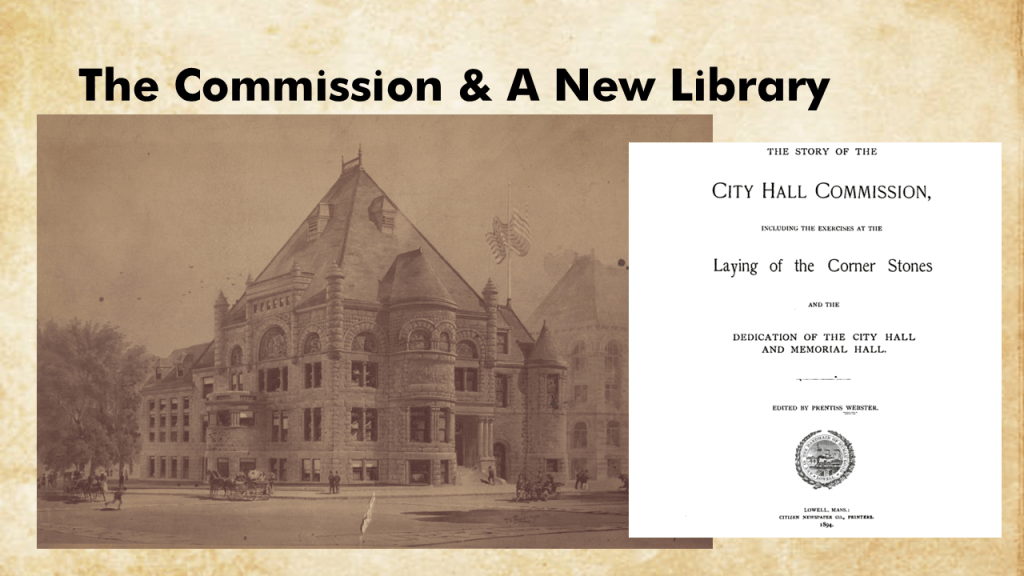

Pollard Memorial Library

As the city began to grow, it was determined that there were a number of needs for city business before the turn of the 20th century. As such, there were multiple arguments for a large more robust City Hall, a place for Civil War Veterans to meet, and also a large library for all residents. Thus began the quest for the architect of the combined City Hall and Memorial Hall/Library project. This contest ended up being a fairly muddy process and I could easily offer another hour explanation about this, but I do highly recommend Joe Orfant’s blog about the controversies of this process. When everything was finalized, Frederick Stickney was selected as the architect for Memorial Hall and the library was constructed in a Richardsonian Romanesque style. One of the first actual documented controversies about the library building was the Corner Store laying on October 10, 1890. Catholic clergy in the area were protesting the Masonic rite of cornerstone laying.

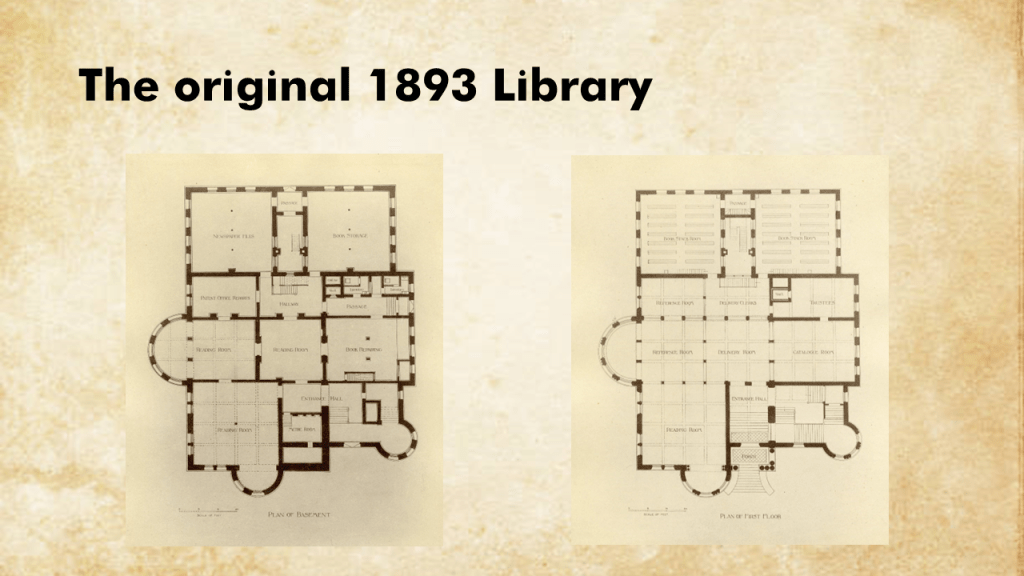

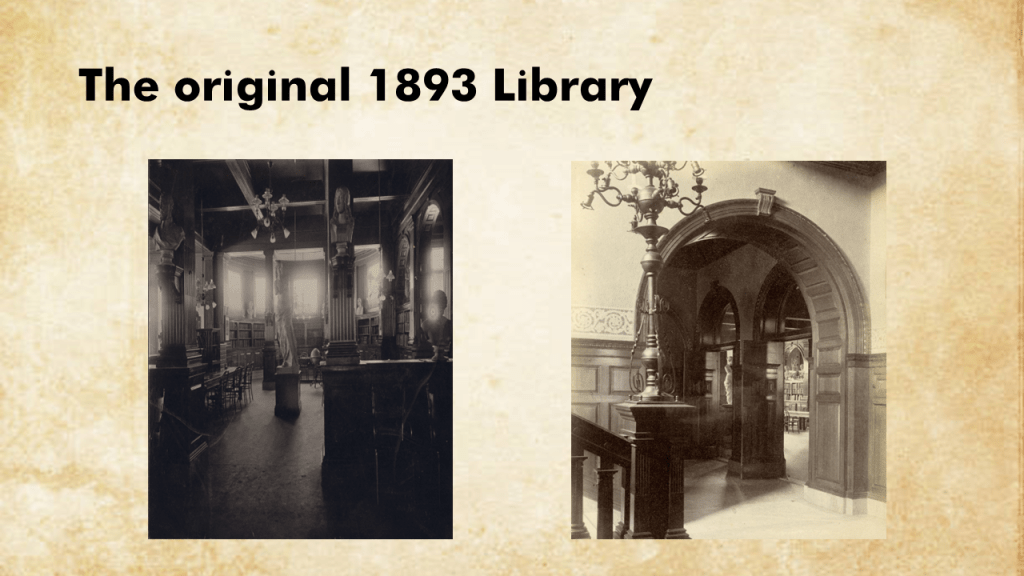

The current library when it first opened was only the ground and first floors with the stacks in the back of the building. Memorial Hall the third floor space above it were not used by the public. There were a number of reading rooms, newspaper files, reference room, and other file spaces for the public. The stacks were closed and anyone requesting an item, needed to put a request in with the delivery clerks.

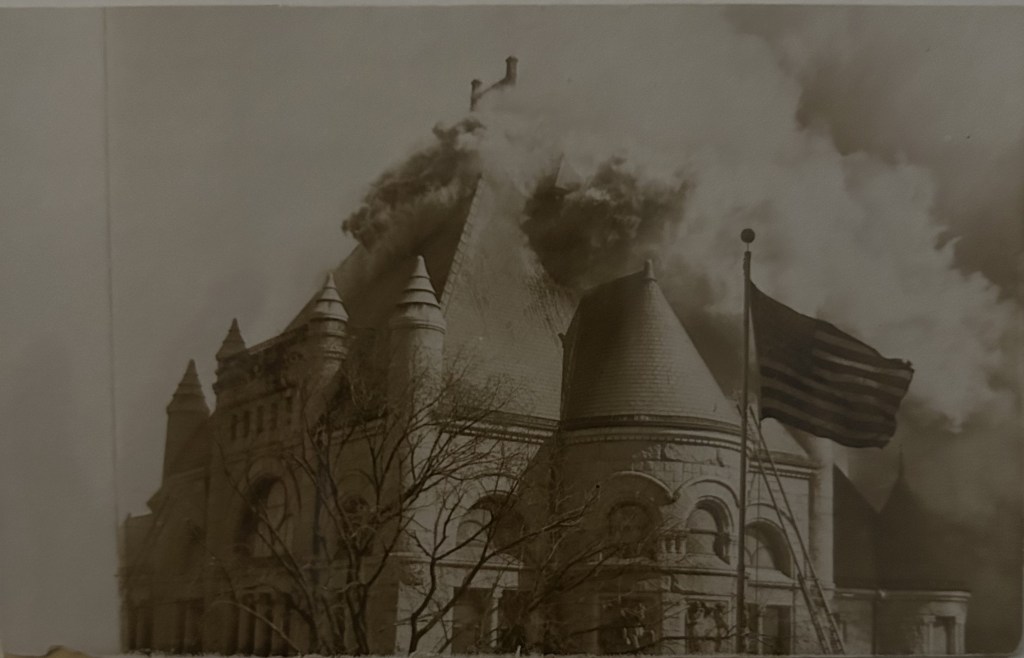

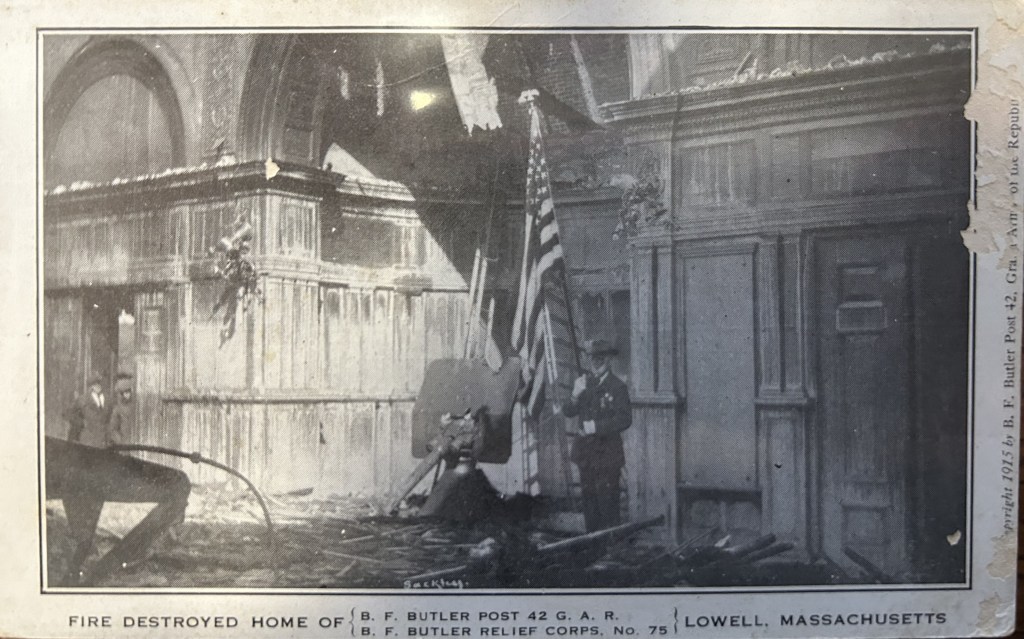

The library remained majorly unchanged until 1915. Midmorning on March 1, 1915 a fire started in the upper level card/smoking room on the third floor in a space above Memorial Hall. There were multiple theories including unattended smoking materials, faulty wiring, but the wire inspector disputed that. Memorial Hall was a complete loss and Civil War artifacts were lost. The Lowell Historical Society, which was in what is now the Directors’ Office had archives and artifacts affected (they still have some books that smell of the fire in their collection). The rebuild was taken shortly after and Memorial Hall was changed from the original design.

When the rebuild occurred, the newly formed Lowell Art Association was called in to assist with the art for Memorial Hall. They advocated on behalf of the city to acquire the three murals by Paul Phillipoteaux that hang in memorial hall today. While newspaper articles estimate that Phillipoteaux was paid $1 million in the early 1880s for the collection, the library was able to purchase the murals for $500 each.

Throughout the library’s history, art has been a very important and integral part of the library. Various donations were accepted and shared with the community. At our earliest opening, we had a Venus de Milo in the first floor reference room. The trustees are responsible for the art in the library, but staff do their best to protect these assets for the city. In an October 28, 1893 Lowell Sun article, there was a notation that “City Librarian Chase has placed a sign “Hands Off” on the Venus de Milo statue in the city library. Anybody can see that the hands are off without the need of the sign.”

If you’d like to learn more about the library’s art, I recommend that you visit our webpage and search for the Doors Open Lowell Tour, which goes into detail about the art, artists, donors, and more related to each piece.

The library has continued to evolve over the years, including becoming part of the Eastern Regional Library System in 1967, then part of the Merrimack Valley Library Consortium in 1982.

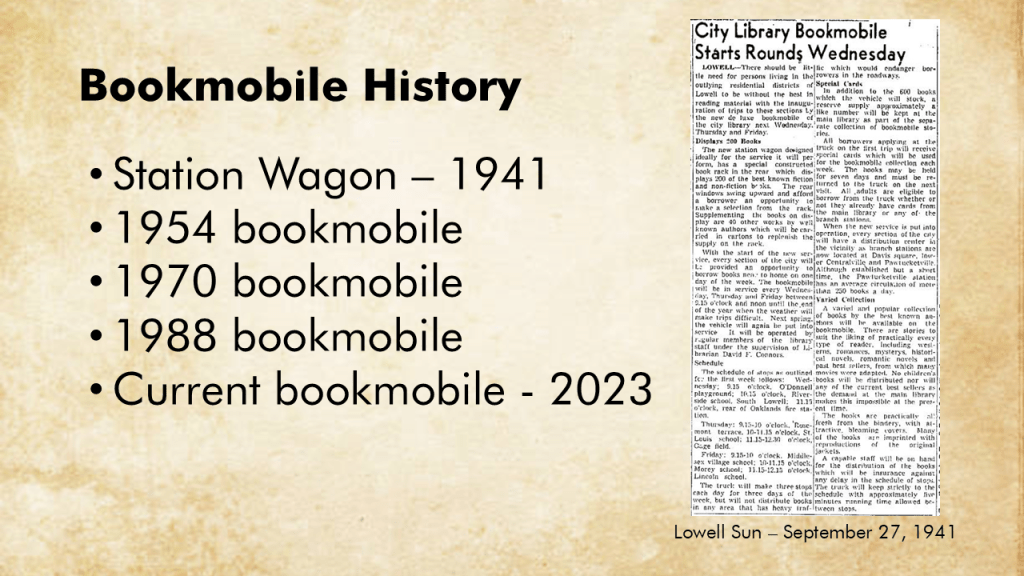

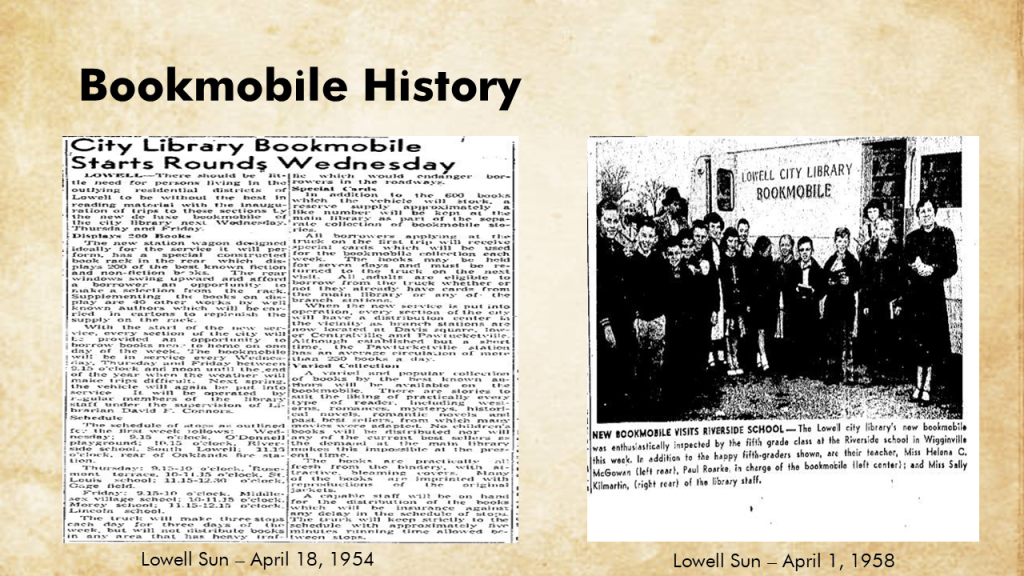

We also have confirmation of at least 5 bookmobiles over our history. The original was a station wagon that started service in 1941, then various bookmobiles were introduced and ran for a number of years, starting 1954, 1970, and 1988. After a nearly 20 year gap, the newest bookmobile was introduced in 2023 and we just celebrated the 1-year anniversary of it being on the road.

While our library and its impact has been documented in various places, here is a selection of writings from various Lowell residents.

Throughout our timeline, there have been questions about book banning, censorship, and other issues related to the items within the library walls. At times, the leadership of the library was deliberately not selecting items requested by other religious groups, even though they were a large selection of the community (i.e. the Protestant leadership ignoring the Catholics, and then the predominance of Catholic representation versus the Protestant).

Another situation involved General Benjamin Butler. History has a love-hate relationship with Butler, but he definitely was not a fan of having his book in the library. Various newspapers documented that he would be prosecuting libraries that carried a copy of his book. It seems to be related to the fact that he wanted to ensure that his copies were purchased by readers directly.

The library, while supported by the city, has two additional nonprofits that support us. We are grateful to the Friends and Foundation who host fundraisers, sponsor programs like our museum passes, arts and crafts, and more to guarantee that we are able to provide great opportunities for our community. We are also grateful for the many City departments, academic institutions, businesses and local nonprofits who provide us with guidance, support, ideas, space, and more to offer unique experiences to Lowell residents.

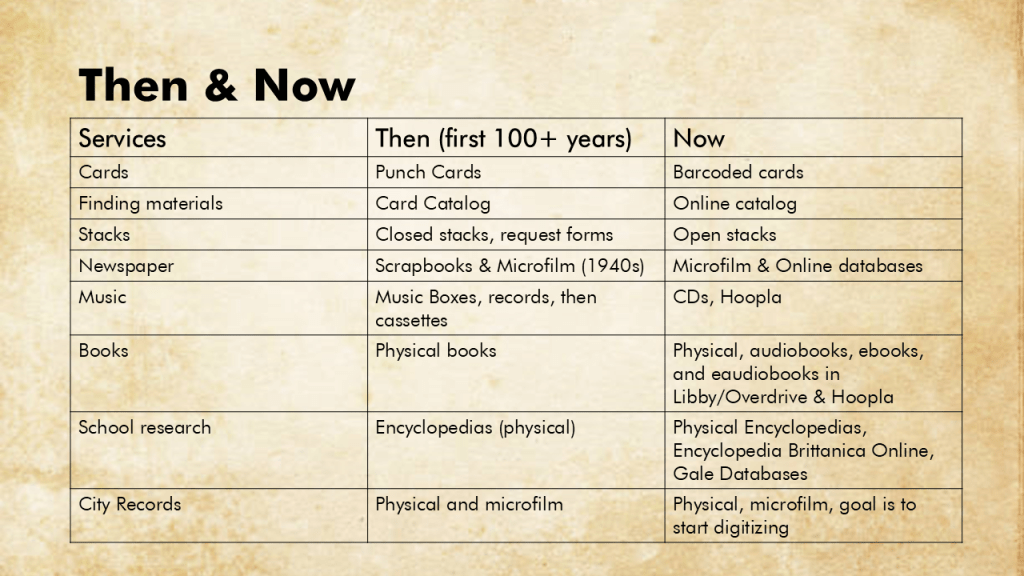

The evolving technology and service models of libraries have been changing and moving with the times. Technology has been incorporated in libraries for the past 40-50 years to ensure that information is being made available as quickly as possible.

As a new director, I will never live up to the expectations of the first library director, Josiah Hubbard.

Today’s Libraries

Besides the Pollard, the following libraries permit access to various materials to the public within the city limits:

- O’Leary Library at UMass Lowell – 61 Wilder Street

- Lydon Library at UMass Lowell – 84 University Ave.

- Center for Lowell History (by appointment) –

- Middlesex Community College Library – 50 Kearney Square

- Lowell Law Library – 370 Jackson Street